This article provides an overview of the tactical map tool and specific examples of its use. It was published in The Nonprofit Quarterly, Summer 2009 edition (www.npqmag.org).

Tactical Mapping: How Nonprofits Can Identify the Levers of Change

by Douglas A. Johnson and Nancy L. Pearson

In the fourth century b.c., Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu said that good strategy is based on three sources of knowledge: knowing your adversary, knowing yourself, and knowing the terrain. It is relatively easy to understand what Sun Tzu means by knowing your adversary. As we analyze ourselves and our allies, we perhaps do less than we should to understand our capability to act. But when adversaries don’t fight the battle on a particular geographic field but instead within complex social structures, how does one understand the terrain?

“Tactical mapping” is a method for visualizing the terrain and, once the terrain is understood, serves as a planning tool for building more comprehensive strategies and for coordination with allies.

Human Rights Tactical Mapping

Tactical mapping is a method of visualizing the relationships and institutions that surround, receive benefit from, and sustain human-rights abuses (although this article focuses specifically on human rights, tactical mapping can also be used for a range of issues on which nonprofits work). The emphasis is on relationships between people and institutions (rather than on concepts or “causes” of human-rights violations). Through these relationships, decisions are made, incentives are given or taken away, and actions are taken. Diagramming these relationships thus creates a picture that represents a social space.

When this diagram is sketched out, it becomes possible for actors to select appropriate targets for intervention and to map actors’ possible tactics to influence issues of concern. Thus the map generates a process flow to plan and monitor how a tactic might function and which relationships it should influence to effectively intervene. Because multiple groups can use the diagram to map their respective targets and interventions, the tactical map becomes a coordinating tool that creates a more comprehensive strategy than is possible when groups act independently. Below we provide a brief overview to help illustrate and conceptualize the various relationships contained in a tactical map.

The Development of Tactical Mapping

The tactical mapping technique is part of the New Tactics in Human Rights Project initiated by the Center for Victims of Torture (CVT). The project has developed several practical resources for human-rights advocates, including an online, searchable database, “tactical notebooks,” training sessions, and more (see “New Tactics in Human Rights Resources” on page 93).

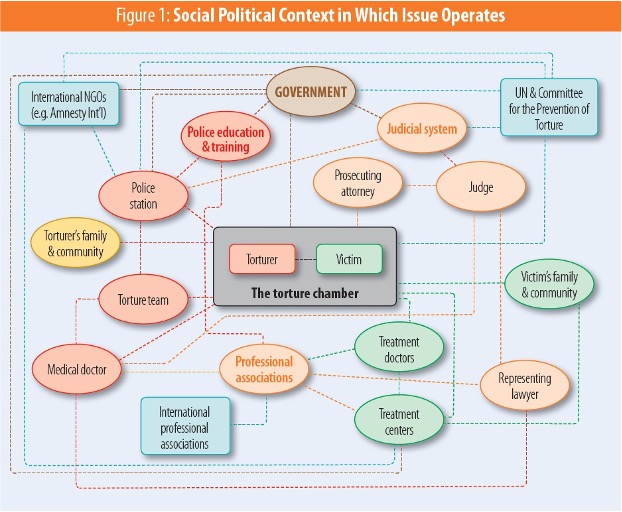

In 1998, with support from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), CVT assembled a working group of experts to consider the persistent nature of torture. The group began by focusing on the relationship between torturer and victim and how the dynamics of this dyad are embedded, sustained, and protected. The group considered the relationships of the victim and those of the perpetrator for possible avenues of intervention. It identified and diagrammed more than 400 relationships, from those at the local to those at the international level (see figure 1 on page 94, which illustrates some of these relationships).

After diagramming these relationships, the working group made a list of current tactics to prevent torture and used the diagram to understand whether these tactics prevented the “primary relationship” of torture. Amnesty International’s method of sending letters to heads of state, for example, presumes a set of relationships and a head of state’s ability to have impact all the way down the line to the police station. By following this chain of relationships, the group speculated on where its force could be undermined, and it considered additional, reinforcing tactics to target those points of breakdown.

The tactic of on-site police inspections (which International Committee of the Red Cross and the Committee for the Prevention of Torture use), for example, operates within a different set of institutional relationships in the target country. The working group followed various tactics from their points of intervention, the relationships they affect, and the chain of relationships they must affect to disrupt the torture dyad. This process of following the tactic’s impact within the system was termed tactical mapping.

By diagramming these vast relationships, it became clear that human-rights abuses are sustained by complex systems of relationships that reinforce one another and support the role of the abuser. Some of these relationships are hierarchical or structured; others are informal. Each of these relationships is a potential site for intervention to prevent torture that requires its own tactic to have the greatest effect.

As the group examined the tactics in use, it also became clear that most human-rights organizations use only one or two primary tactics. In addition, implementing a new tactic often involves a steep learning curve and significant investment in staffing; organizations lack experience on how to measure tactics’ effectiveness, and funds are often tied to the tactics for which the organization is known. Thus, institutional investments are usually directed at doing what we do more effectively rather than at learning new tactics.

This problem is compounded by developing interventions with little coordination between organizations. In any complex system, limited tactics can affect only narrow targets. Without coordinated effort, other parts of the system are free to use their resources to protect the target under pressure. The working group came to believe that this dynamic helps explain the persistent nature of torture.

If human-rights abuses don’t yield to a single tactic and if most organizations can employ only one or two tactics, combating human-rights abuses requires a larger, collaborative strategy to disrupt the system of relationships in which these abuses are embedded. The tactical mapping process also provided insight into how a more coordinated strategy can emerge when we understand how tactics relate synergistically or conflict with one another.

The process of mapping the tactics in play exposed large areas of the map unengaged in the struggle to prevent torture (such as among the families, friends, and social networks of perpetrators) and where new methods could stimulate more extensive pressure. The group hypothesized that every relationship within the tactical map was a potential target to launch an initiative but that not all tactics were appropriate for each actor. This called for a wider selection of available tactics and was a major impetus for the development of the New Tactics in Human Rights Project.1

Figure 1 the different kinds and levels of relationships identified in the original CVT–New Tactics tactical map. Relationships range from the “torturer-victim” relationship and relationships that surround it, including those internal to a region, such as a country’s judicial system and police institutions, as well as connections external to a region, including associations, nongovernmental organizations, and intergovernmental systems.

Figure 1 the different kinds and levels of relationships identified in the original CVT–New Tactics tactical map. Relationships range from the “torturer-victim” relationship and relationships that surround it, including those internal to a region, such as a country’s judicial system and police institutions, as well as connections external to a region, including associations, nongovernmental organizations, and intergovernmental systems.

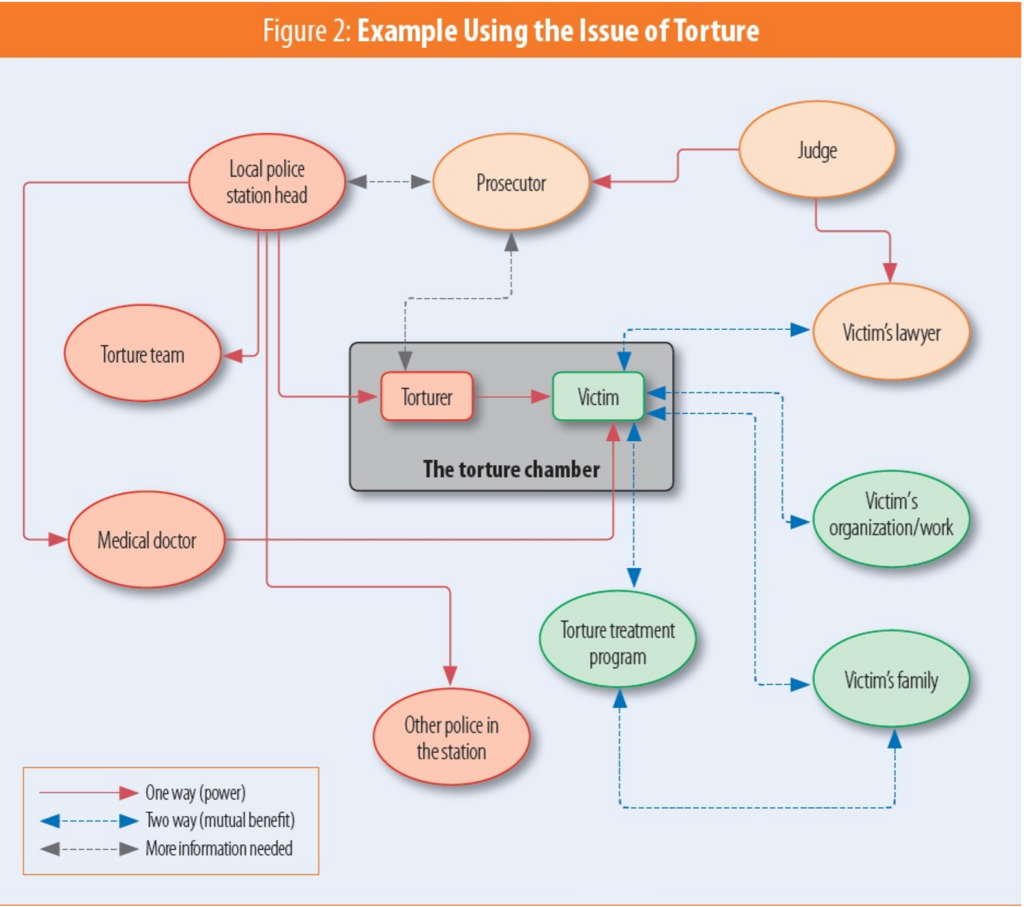

Nevertheless, large parts of the map are relevant for understanding many torture scenarios. Whether the torture occurs in a police station, an army barracks, a military camp, or elsewhere, the government’s international obligations and international relationships, the structure of government authority, and formal and informal social relationships in a particular culture are all relevant. In a given country, the lines of authority vary depending on which control structures are the primary culprits in the use of torture. This insight makes large parts of the map significant in understanding these differing scenarios (see figure 2 on page 95).

This initial work demonstrates the tool’s potential in planning an anti-torture campaign. The mapping exercise demonstrates that many tactics currently in use require a lengthy chain of impact to be effective; this raises questions about how robust they are. The map also analyzes the presumed effect of tactics. The mapping process suggests that, by understanding causal links, more can be done to improve the effectiveness of tactics. Finally, the map itself permits creative brainstorming on new tactics, which can stimulate local action.2

In various training workshops with human-rights participants, the tactical mapping tool has identified relationships and developed tactics to address a spectrum of human-rights violations.3

How Does Tactical Mapping Work?

The tactical map helps gain a deeper understanding of issues, such as the following:

- the complexity of relationships involved in the issue;

- potential target points for intervention;

- potential allies and opponents;

- the improvement of tactics planning (current and potential);

- the ability to track the effectiveness of tactics to move strategy forward;

- the ability to enhance strategic and tactical adjustments; and

- the coordination of allies and their tactical contributions.

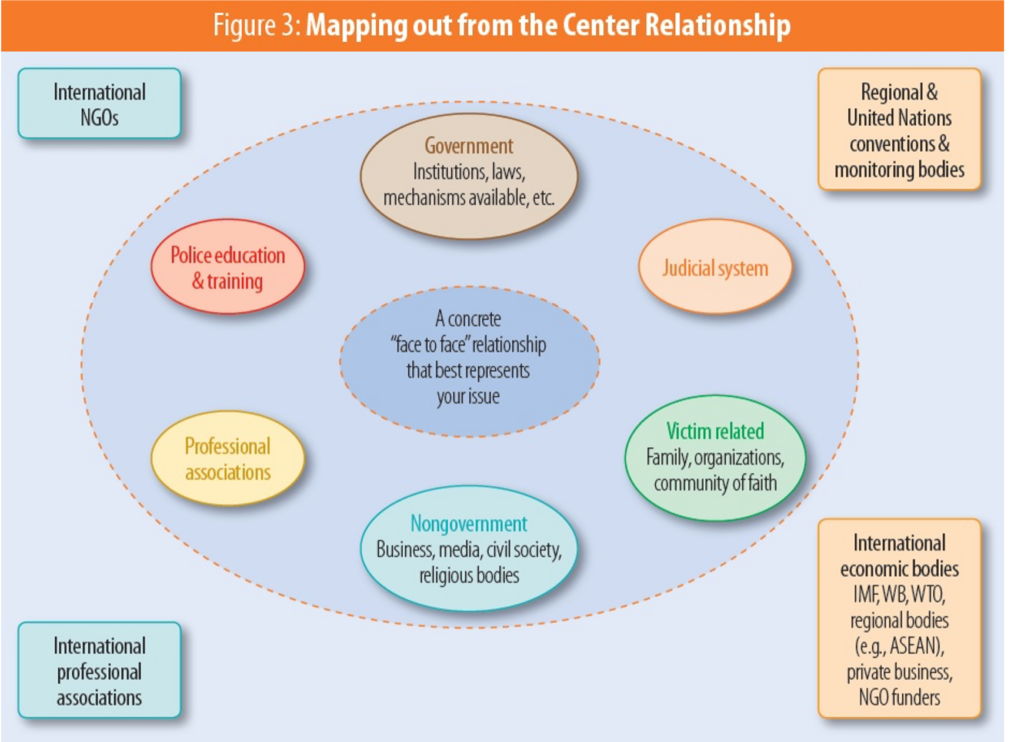

Note that the figures in this article provide a sample of the mapping process by illustrating relationships at various levels of interaction. The mapping process, for example, begins by identifying the direct “face to face” contact in the identified center relationship. It is important to begin with a concrete relationship that best represents the problem (see figure 2). After mapping face-to-face contacts, identify relationships that are further away but that have an interest, investment, or impact on the center relationship at the local, national, regional, and even international levels (see figure 3 on page 96).

The process begins by understanding the relationship(s) that an issue or “campaign” seeks to change (such as the relationship between a torturer and a victim), then diagramming the relationships in which this strategic target is embedded. The tactical mapping tool uses a series of symbols comparable to a flowchart or organizational diagram. Participants have sketched maps in an afternoon or more extensively over weeks to plan a national campaign. The Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly (hCa) in Turkey has created the most extensive mapping to date. Over an 18-month period and in consultation with the New Tactics Project, hCa convened government agencies and nongovernmental organizations to develop a comprehensive STRA-MAP (or strategic map) concerning torture in Turkey.4

Although the generic map provides insight, the real value of the method is its application to particular problems, countries, and locales. The more knowledge individuals bring to the process of diagramming the relationships, the more profound are their insights about the problem and solutions. As the information is gathered, especially for a local or national campaign, campaign leaders should create a “database” (which may range from simple forms such as index cards to complex computer programs) to monitor the spectrum of relationships at each node in the map that offers the potential for intervention. The nature of the relationship should also be noted: Is it one of influence or one of command and control? Is it one of regard or animosity and competition?

As the tactical map has grown and developed, its contributors have added color-coded lines to illustrate the nature of these relationships. Figure 4 on page 97 features an example of a 2006 tactical map process hosted by CVT regarding U.S torture at Guantánamo Bay.

The first task is to map the inner “circle” of relationships. Those relationships are closest to the center and have a direct face-to-face relationship with the center.

The first task is to map the inner “circle” of relationships. Those relationships are closest to the center and have a direct face-to-face relationship with the center.

Determining the nature of relationships provides insight into potential tactics. If a minister of the interior, for example, has the authority to make policy and assert control over torture, campaign planners should understand the relationships that influence his decision making (in figure 4, a one-way directional red arrow line, for example, shows the “power” relationships in the Guantánamo Bay situation). Some influence comes from below, some from above. But there may be other relationships that shape the minister’s world view, such as a former military comrade, spouse, or religious leader (in figure 4, a bidirectional blue arrow shows mutual benefit). In situations where corruption or exploitation is a concern, an arrow indicates an actor that uses a position for gain, which may also represent a relationship (figure 4 depicts this dual set of relationships with a one-way directional green arrow).

In our interior minister’s example, knowledge of these relationships could inspire new approaches to gain the minister’s commitment to stop torture. Having team members from multiple organizations and backgrounds provides further depth to the analysis of this web of relationships. Where more information is needed regarding a relationship, the use of gray dotted lines can serve as a reminder. Participants in the Guantánamo Bay tactical mapping process proposed an additional “conflict” line. Such a line may convey conflicts of interest or personality or other conflicts among multiple departments or agencies. During the Guantánamo Bay mapping process, for example, participants highlighted the interagency “conflict” between the military and the FBI’s concerns about how prisoners were treated.

The ability to redraw the visual map based on changes discovered through data gathering helps monitor areas of progress and new opportunities or threats to a campaign against torture. When a map depicts different levels of detail, the coordinating group can monitor the major intervention systems, and organizations can take responsibility for a particular area of the map. In the case of the interior ministry example, a more detailed map of the ministry and its surrounding web of relationships would be a next step for planning a tactical intervention.

Modeling Problem Development

As we act in the world, we begin to change it. Sometimes an action hardens the opposition; sometimes it helps convert an individual to protect human rights. In some cases, only the people at an institution change; in other cases, institutions develop new mandates and policies. The tactical map focuses on individuals and institutions, not concepts. These ideas change during a campaign and simply by virtue of the passage of time. Understanding the individuals and the nature of their relationships with others requires investigation, research, and tactical flexibility.5

To be most useful, a tactical map must be dynamic and constantly updated to derive the insight to plan and monitor strategies and tactics. From a research standpoint, the tactical mapping process provides concrete, reusable information in existing and future contexts. The following are some of the applications of a dynamic map:

- It serves as a documenting tool to monitor the implementation of a specific tactic, enabling the actors to identify points of strength and weakness to deploy resources and activities dynamically.

- By providing a repository of relational networks and associated tactics that other actors can use in similar situations, the mapping tool serves the larger context of generating strategic thinking within the human-rights community at large.

- By identifying the complex relationships involved in human-rights issues, organizations benefit greatly from such research systems.

- By coupling this information with a tactical mapping tool, civil-society organizations, international organizations, and governments can better use the data to develop more comprehensive strategies to combat human-rights abuses.

Once the tactical map diagram is “complete,” it can then “map tactics” and create understanding about which relationship(s) each tactic is expected to affect and how.

The process of mapping relationships and identifying current and potential tactics creates a diagnosis of the situation in a given context, including the key relationships surrounding human-rights abuses, the impact of existing tactics, and additional targets in need of intervention. Consider that a torturer is connected organizationally, professionally, and socially. In order to create change within these various relationships, it is important to understand which individuals or organizations can do so already or be put in place to do so. A tactic, for example, may target the torturers’ membership in a police union or association, which may in turn provide an opportunity to work through professional associations that reach across national boundaries, thus exerting pressure from within and outside.

Mapping these relationships can be done with simple tools at the grassroots level: with a stick to outline relationships in the dirt, with Post-its, or on paper with colored pens. A class of students at the University of Iowa, for example, used a Post-it method to highlight concern about a sexual harassment incident on campus. The tactical map tool provides an excellent medium for seasoned human-rights advocates and students in analyzing their terrain to determine options for action.

The second task is to map relationships that affect the center but don’t have a direct relationship with the “center” relationship (see ovals). The third task is to map the international or external relationships that affect the center relationships (see rectangles).

The second task is to map relationships that affect the center but don’t have a direct relationship with the “center” relationship (see ovals). The third task is to map the international or external relationships that affect the center relationships (see rectangles).

The development of more technological tools, such as database systems, to house the research collected and feed this wealth of information into a tactical mapping program would greatly increase the adaptability and response time for significant change in the human-rights arena.

Each of these contexts requires ongoing research to understand the systems and people involved in human-rights abuses—and that means those who make bad decisions as well as those who could protect human rights. Certainly, activists on the ground have begun to collect this information. Building collaborative partnerships with sociologists, political scientists, and other academics can help enhance this research. New Tactics is especially interested in documenting tactical interventions and evaluating their results so that others can gain insight into possible interventions for their own settings.

In our experience, the tactical mapping approach has proved effective for human- rights practitioners as they gain a new perspective to develop strategic efforts to end human-rights abuses. The process offers greater clarity about the situation being mapped, anticipates potential responses, identifies areas for additional attention and collaboration, improves coordination, and provides an effective tool for assessment and evaluation.

In November 2006, the Center for Victims of Torture gathered representatives from 13

In November 2006, the Center for Victims of Torture gathered representatives from 13

organizations to use the tactical map tool regarding the situation of U.S. torture at Guantánamo Bay. This “first level” aspect of the tactical map features colored lines to identify relationship dynamics.

Examples of the Tactical Mapping Tool

As part of a New Tactics–National Endowment for Democracy–sponsored grant, two organizations used the tactical map tool to expand their understanding of an issue and to collaborate with other organizations.

During a training conducted by Liberia National Law Enforcement Association (LINLEA) in 2006, the organization introduced the New Tactics tactical mapping method to explore a post-conflict issue in Liberia: “mob justice.”

Key factors identified by the trainees as contributing to mob justice included lack of trust and confidence by a great percentage of the citizens on the effectiveness of the criminal justice system of Liberia. Many citizens would prefer taking the law into their own hands instead of turning over suspects to the police because they feel that the police [are] ineffective (the police lack logistics and adequate training), or even if the suspects are arrested and turned over to the courts there are delays in court trials, and most often suspects are released after bail. In addition citizens are charged with exorbitant court fees, which discourage[s] many persons from pursuing court cases. It was also noted that the corrections component was not providing the necessary rehabilitative programs for inmates when incarcerated in prisons.6

By using the tactical mapping method, the trainees identified several activities for tactical intervention, including the following:

- training, developing, and professionalizing the Liberia criminal-justice system;

- providing community education and awareness on the concept of the rule of law and the dangers of mob justice;

- building effective community structures, such as neighborhood-watch teams, to promote crime prevention and the rule of law;

- training of community members to monitor and report mob action and human-rights violations;

- introducing and developing models of community policing; and

- prosecuting perpetrators of mob justice.

The EvAran, Mongolia, project team used the tactical mapping tool to examine torture in Mongolia. By drawing a picture of the sociopolitical framework of torture, the first mapping workshop yielded positive results and proposed future collective action. During the course of consultations with more than 25 organizations, the organization used the tool to address other human-rights issues. In September 2006, the EvAran project team organized a workshop to introduce the tactical mapping technique to the broader human-rights community.

The participants of the mapping workshop included human-rights practitioners and private attorneys engaged in a public-interest litigation case to seek compensation for environmental and livelihood damages caused from extractive mining practices. From the workings of the mapping workshop, it became evident that one of the main causes for difficulties in the overall litigation process—apart from corrupt local administration that back[s] mining companies and low community awareness to collectively claim rights—was lack of judicial precedent and reference tools for the defense to quantify damages endured from environmental degradation and loss of livelihoods for the herder community. The following tactics were proposed for serious discussion after the workshop: (a) engagement of specialists from the state professional inspection agency and other relevant authorities to develop guidelines for environmental assessment of exploration damages; and (b) organization of a roundtable meeting to sensitize the judiciary on human rights of herder groups.7

This application of the tool explored possibilities for future collaboration of civil-society actors to promote and protect the human rights of herder groups at extractive mining sites and resulted in the development of tactics that had not been considered to uphold these rights.

In November 2006, CVT and New Tactics gathered a group of representatives of 13 U.S.-based organizations working on the issue of U.S. torture at Guantánamo Bay. We provided a draft tactical map based on our knowledge of the situation. This saved group time and made it possible to more deeply examine different areas of the map where other organizations had greater expertise and knowledge. The participating organizations gained additional benefits, including the following:

- Gathering collective information. The process revealed new information and relationships that enriched the map and knowledge among the group.

- Discovering common targets and tactics. Two groups had a grant by the same foundation to write about the impact on Guantánamo prisoners (from the legal and medical/psychological perspectives). They collaborated and wrote a comprehensive report that has been one of the few resources cited and used on Capitol Hill. Two other groups that had planned action in Washington, D.C., on the same day worked together to expand the scope of each group’s action.

- Building new collaborations. Several organizations forged stronger alliances that led to new campaign actions.

In July 2007, CVT’s New Neighbors, Hidden Scars project used the tactical map tool to examine and evaluate the progress toward building an effective health-provider network for refugees in a Minnesota community (see figure 5 on page 98). As the project neared its end, the visual tactical map tool provided focus on the remaining steps required for bringing together health-care providers and refugee groups to deliver better health-care services to the refugee community.

Over the course of just a few years, the tactical mapping tool has provided numerous organizations with a fresh outlook on how to prevent torture. It provides not only a means to visualize the web of relationships in which human-rights abuses occur but also concrete new tactics to combat these violations. By starting from a place of knowledge gathering and visualization, the tactical mapping tool has provided human-rights activists with a new vantage point to understand their opponents and to support the victims of human-rights abuses.

Figure 5 provides an example of how to use tactical mapping to depict a state-level organization’s internal and external relationships.

Figure 5 provides an example of how to use tactical mapping to depict a state-level organization’s internal and external relationships.

Endnotes

- See the New Tactics in Human Rights Web site at www.newtactics.org.

- “A Case in Point: Using the Tactical Map” on the New Tactics in Human Rights Web site provides examples that illustrate the points of tactical intervention (www.newtactics.org/sites/newtactics.org/files/tools/a_case_in_point_en_1-16-09.pdf).

- Two examples are available on the New Tactics in Human Rights Web site: a tactical map on domestic violence developed at the Asian New Tactics cross-training workshop in August 2005 (see www.newtactics.org/sites/newtactics.org/files/resources/Sample_Map.JPG) and its application in Nigeria to address campaign plans on the treatment of wives and widows (see www.newtactics.org/en/node/5671, and for the full Nigeria report, see www.newtactics.org).

- For more information and an online version of the map—currently only in Turkish— see www.stramap.org/tr/anasayfa.aspx.

- Douglas A. Johnson, “The Need for New Tactics,” New Tactics in Human Rights, September 2004 (www.newtactics.org/sites/newtactics.org/files/resources/Need_for_New_Tactics_Article.pdf).

- The LINLEA example was quoted and summarized from the final grant report provided to New Tactics in September 2006.

- The example was summarized from the final grant report provided to New Tactics, September 2006.

Douglas A. Johnson is the executive director of the Center for Victims of Torture and Nancy L. Pearson is the project manager of the New Tactics in Human Rights Project. Scott Hvizdos, the assistant director of development at CVT, also contributed to the development of this article. For more information, visit the Web site (www.newtactics.org) or e-mail us at [email protected].

To comment on this article, write to us at [email protected]. Order reprints from http://store.nonprofitquarterly.org, using code 160216.

Download the Article as a PDF: